Charles Goodyear circa 1835

The Rise of Goodyear and the "New Slavery"[]

Needless to say, Charles Goodyear was held up as the ideal "American" by the Union government. His racist, revanchist, xenophobic rantings made sure the scientific genius's portrait was hanging up in public schools around the country, right next to those of Jesus Christ, Julius Caesar, and Elizabeth I (who had recently experienced a new wave of popularity as an "anti-Spaniard Christian leader"). He was for all basic purposes a lunatic--a lunatic idolized by the masses and carried on shoulders into Boston upon his arrival from Berlin. His face was everywhere, and so to was his promise to Friedrich-Wilhelm III that America's industry would never be outdone.

Ever since its formation, the Republican Union had long been falling behind its neighbors in industrial matters. In 1828, the Union had ended slavery forever (largely to just annoy the Southrons and show how "enlightened" they were). The Southron republics, meanwhile, still used black slaves to work in their increasingly advanced factories. Newport News, widely considered the industrial capital of North America at the time, employed immigrant workers, promoting further immigration, while they used slaves to build the factories to begin with. In the Union, in late 1833, Goodyear finally came to Philadelphia touting his new book, Plans for Rapid and Stable Industrial Growth and the Maximization of Profit. The long-winded tome called for harsh immigrant labor was read widely by government officials, who proclaimed it a work of art. He was brought before an Inter-State Committee to discuss how best to institute these ideas. With his pockets loaded with government money, Goodyear turned to Shicagwa, the growing Iowai port city on Lake Michigan, as his main target.

The way Goodyear abused the workers he hired was, in many ways, much worse than actual slavery. In the South, thanks to a growing movement for eventual abolition, the slaves were recently being treated very well in most places. However, up in locales like the Goodyear Shirt and Blouse Company factories, if a worker was a minute late, he or she could be beaten by company thugs. Any attempts to protest poor working conditions were promptly crushed. Goodyear became the "Caesar of Shicagwa" by 1835.

The crazed industrialist was determined to crush the spirits of his foreign employees utterly. Starting in 1835, he launched wave after wave of new companies, many bearing his name, and moved into a palatial mansion in the Iowai countryside. To protect these new interests, he hired a mercenary army of "private eyes" to keep "law and order" in place. Soon, simple company thugs at places like the Goodyear Shirt and Blouse Company and the Goodyear Tools Company were replaced by black-uniformed, baton-wielding soldiers. Any attempt at forming any sort of labor unions were snuffed out by the mercenaries, and thus was born the "New Slavery" in the Union.

The New Slavery movement arose from the bizarre mentality and outlook of Union citizens on foreigners, especially Catholics or Eastern Europeans. Since the early 1820s, the government had been actively tricking impoverished Europeans into coming to the "Land of Opportunity." The way it worked was that Union agents would sail to Europe and outright lie to the poor people, and instruct them on how to cheaply travel to America. For many of these people, for instance, the young Serbian Dragomir Crncevic, they spent all they had on the trip.

Crncevic's story was later turned into a novel in Virginia and became a best-seller under the title Dragomir's Cabin. The first portion of the book tells how Crncevic's parents and only brother were killed in the Great Wars of the Empire. Then, starving in the midst of the Serbian Famine of 1835, the young man meets an American named Theodore Jones, a traveling medicine and sideshow man and secret recruiting agent working for the Union, who promises him wealth and abundance in "Dear America." Fooled completely and with just enough money to make the trip as a crewman on a Union vessel in the Mediterranean, Dragomir sails to Boston.

Upon his arrival, though, he is met with hatred and slurs, and within two days of being a Union citizen has been mugged twice. Understanding little English, he is hired for menial labor by the new Boston-Shicagwa Rail Company, a new subsidiary of Goodyear Rail aiming to connect the opposite sides of the nation with railroads. He is routinely beaten by Goodyear's mercenaries for sometimes no apparent reason. Finally, after attacking an abusive guard, both of his legs are broken and he's sent to the "Foreigner Prisons" in Pennsylvania's Ohio region. There, at Camp Burr, he recovers from his injuries and is then forced to relocate to Shicagwa, to work on an the expansive construction site for the new town hall. There he joins a strike.

The Christmas Day Strike Massacre of 1837

On Christmas Day, 1837, the workers all quit. The mercenaries marched in, carrying muskets and rifles. Goodyear sent his vice-president, Samuel Morse, in to order the workers to stand down. When they refused, Morse unhesitatingly ordered the small army to open fire, beginning the Christmas Day Strike Massacre of 1837. Dozens go down in seconds, and Crncevic is hit in both legs by musket balls. Doctors haphazardly amputate the legs and he is then sent back to Camp Burr. There, for the last several months of his life, he sits in his "cabin" (actually a shack) penning his story. After he managed to get the writing smuggled out, he died of infection from his double amputation.

The heart-wrenching biography sold like wildfire in the Southron republics, only beaten in sales by the Bible. Many international clubs and organizations were formed to press for reform in the Union.

Goodyear Carriage Company Strike of 1838

The Union responded by decrying the book as "Southron subversive propaganda," and promptly outlawed it. Then, the government turned right around and gave Goodyear the honorary title of "Colonel," reflecting the high esteem in which they held the industrialist. Colonel Goodyear Enterprises was born, and from that point on, Goodyear finally lost whatever remaining bits of morality he had. Brutality was the rule of the day, and absolutely nothing was to get in his way of modernizing the R.U.. Any forms unions might take were outlawed. Goodyear's mercenary forces grew in leaps and bounds, with uniformed thugs present at every factory.

The Goodyear Rail Company Riots of 1840

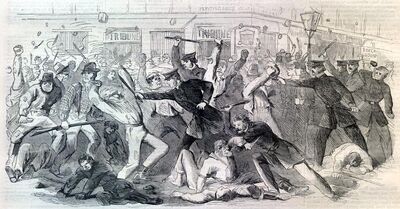

Protesting Irish Colonel Goodyear Enterprises workers in New York City are crushed by the NYPD (1844)